Sometimes it feels like we’re all being subjected to some kind of trauma-Olympics that we just HAVE to partake in. […] There is significant value in creating art not because of our hardships, but despite them. – Jaye Ink

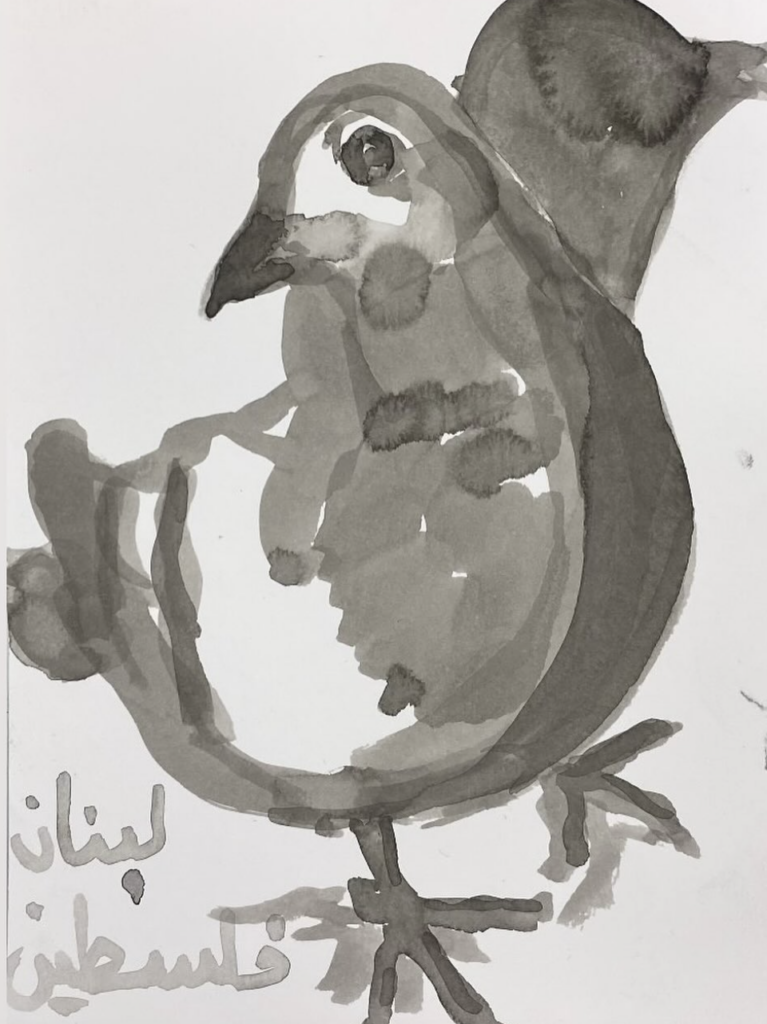

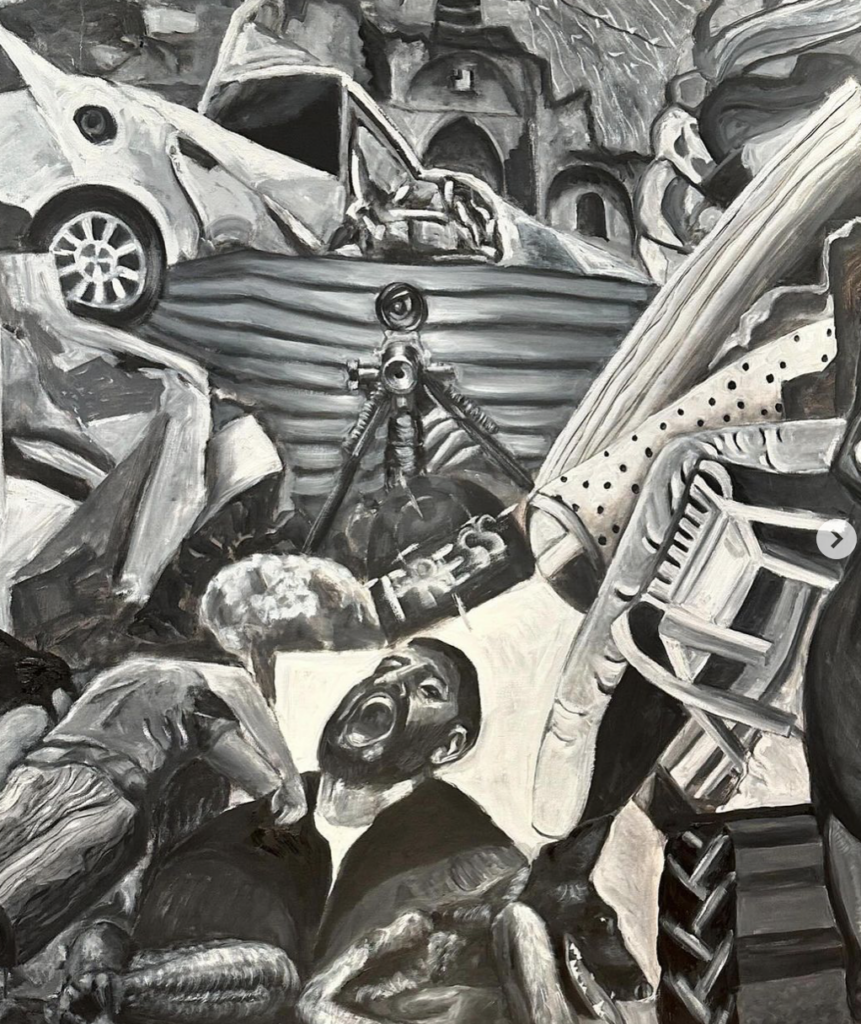

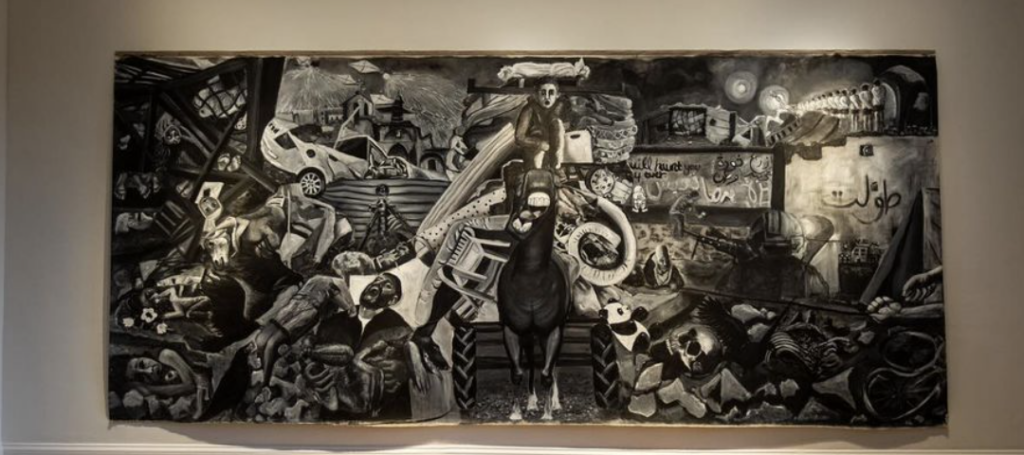

Malak Mattar is a Palestinian artist from Gaza who was recently featured at the Toronto Palestine Film Festival (TPFF), often compared to Frida Khalo. TPFF is a volunteer-run non-profit organization dedicated to bringing Palestinian art, music, food, and cinema to the GTA.

Art is a tool of protest and resistance; to claim otherwise would be an erasure of history. Emory Douglas of the Black Panther Party, the poetry that rose from The Beats Movement and how it was used to protest the Vietnam War, Fairuz switching her focus to sing about Lebanese Resistance, and Banksi’s graffiti on the West Bank wall. The Toronto Palestine Film Festival is another form of this resistance against cultural erasure. They are preserving Palestinian culture and people who are often erased and denied that they ever existed through this festival. TPFF was first showcased in 2008 to commemorate the 60th anniversary of Al-Nakba and just finished their latest run.

Mattar says that working with TPFF gave her a sense of community. She says “Festivals are very important as they amplify the Palestinian narratives and voices through art and culture.” Mattar is a London-based artist from Gaza who has been creating professionally for about 10 years when painting became a way to cope with her trauma during the 2014 Israeli massacre in Gaza.

Her art focuses on portraits where she weaves in pieces that showcase her Palestinian heritage. However, there also is the struggle of needing to be resilient. Part of her new work is to reflect on the nature of human beings regardless of heroic and resilient titles, titles that are often thrown at people suffering. “Idealizing the Palestinian human can also be dehumanizing,” she shares, “It might give one comfort and burden relief to call a suffering human being hero but in fact striving for extreme ways of survival reflect the deep failure of humanity. The question is, can we call a 6-year-old child walking kilometres to fill a water bottle for a family in a tent a resilient child?”

This is something that many BIPOC artists have to grapple with. Speaking to Jaye, a Libyan-American artist, she tells us that resilience, in her art, is about holding onto and celebrating her cultural identity, even when it feels threatened or misunderstood. To her, resilience is about “using creativity as a form of resistance, against the erasure of our stories.” However, as artists of colour are given the expectation that they will create surrounding their traumas, like Mattar, Ink finds it limiting. “While I take pride in my Libyan identity and a lot of the stylistic decisions in my art stem from that, it’s not always overt,” she tells us, “I draw inspiration from my heritage but allow myself the freedom to experiment and blend it with other influences, creating a fusion of aesthetics that pushes my work in new directions.”

Ink shared that during a meeting with an art lecturer, she discussed her practice which, at the time, was predominantly focused on food as an art form and a symbol. Upon learning that she is Libyan, she was questioned as to why her work wasn’t directly related to that. She confesses that she felt completely disregarded and that they “reduced my artistic voice to my nationality, implying that my work held no value unless it conformed to the identity they expected of me.” This thought is highlighted by Egyptian singer-songwriter, Hana Yazz, who echoes that, being in the Arab diaspora, there are not enough initiatives such as TPFF.

Integration is a struggle even outside of showcasing their art as BIPOC individuals. Yazz tells us that while places like London are good at allowing cultures to coexist, they do not prioritize integration. Ink reminisces on the outpouring of grief when the Notre Dame Cathedral caught fire or when the Just Stop Oil activists threw soup at the Mona Lisa Painting, yet, “for over a year and long before, we have witnessed a genocide with little condemnation or meaningful action from world leaders or those with the power or platforms to make a difference.” However, Ink shares that “it often feels like if we don’t take these initiatives ourselves as MENA artists, we risk being forgotten by the rest of the world. There seems to be no sense of urgency afforded to us. That’s why these kinds of festivals are important.” Also, rather than isolating MENA art to specific events to showcase their art, mainstream programs must collaborate with diverse curators from the MENA region to ensure authentic cultural context is provided, making sure MENA art is understood and appreciated on its own terms—not exoticized.

I feel like Arabs don’t need to say anything, but that might be me as an Arab saying that. I don’t know if other people expect that and, personally, I don’t care. – Hana Yazz

Finally allowing themselves to overtly embrace their culture brings a fear of unacceptance. Yazz tells us that she’s newly begun integrating the Arabic language into her songs, overcoming a fear of hers. “It’s something outside of my comfort zone,” she confides, “it’s like I’m revealing more personal layers about me and my heritage.” This mirrors Ink’s integration of North African culture which includes jewelry and face tattoos being rooted in North African traditions, particularly among women. Mattar, Ink, and Yazz include their title of resistance in their abilities to create, despite the expectation that they must create based on certain expectations about their identities.

If you’re from somewhere where something bad is happening there should be no expectation on you to say anything. You can process that how you want to process that to be honest, this whole everything that’s happening is the fault of the Western world. – Hana Yazz

Yazz reminds people that they mustn’t cater to specific viewerships based on assumptions. To dampen a culture and heritage or only highlight the traumas imposed is to contribute to erasure. Within the art world, there is a greater push towards initiatives that highlight BIPOC artists and that is because of people like Mattar, Ink, and Yazz as well as initiatives like TPFF regardless of relatability to non-marginalized folks. To highlight traditional art that is not exclusive to trauma allows artists to be more than a single story and expand in their artistry. As Ink says, “While we cannot bring back what has been lost, which is of profound, irreplaceable value, festivals like this ensure that Palestinian voices and culture endure.”