Mens rea and actus reus are the two components of a criminal conviction. The guilty mind and the guilty act. These are the two fundamental elements that must be established in order to convict someone of a crime. However, where does the line blur between creativity and evidence?

Rap lyrics have been used by prosecutors as alleged evidence in criminal cases, putting rappers behind bars. Despite bills being passed limiting the use of lyrics as evidence, it continues to be done. This practice usually targets up-and-coming artists without the notoriety or resources to mount a strong defense. While the scope of the indictments goes far beyond lyrics, the use of a rapper’s lyrics as part of the evidence is what has drawn such pushback from the music industry. Especially when these lyrics are central to the prosecution’s argument and characterized as an admission of sorts.

Violence in music is nothing new nor is it exclusive to rap. Taylor Swift has a song entitled no body, no crime all about how she murders her friend’s cheating husband and gets away with it. Lyrics such as:

“Good thing my daddy made me get a boating license when I was fifteen

And I’ve cleaned enough houses to know how to cover up a scene

Good thing Este’s sister’s gonna swear she was with me

Good thing his mistress took out a big life insurance policy”

Although there probably is no scenario where she would have to sit in front of a jury and explain that, no, she didn’t really kill a man and toss his body overboard. Pop music is allowed exaggeration and the creativity to tell a story. Similarly to how people write books, lyrics and music is an art that is oftentimes made up and/or exaggerated. Surely Donna Tartt wouldn’t be seen having to defend herself against the murder of her university classmate and Colleen Hoover would not get CPS called on her for the Verity journal entries. Referencing rap lyrics in criminal charges is a practice with the implication that they are reflections of reality, discounting rap as a form of artistic expression.

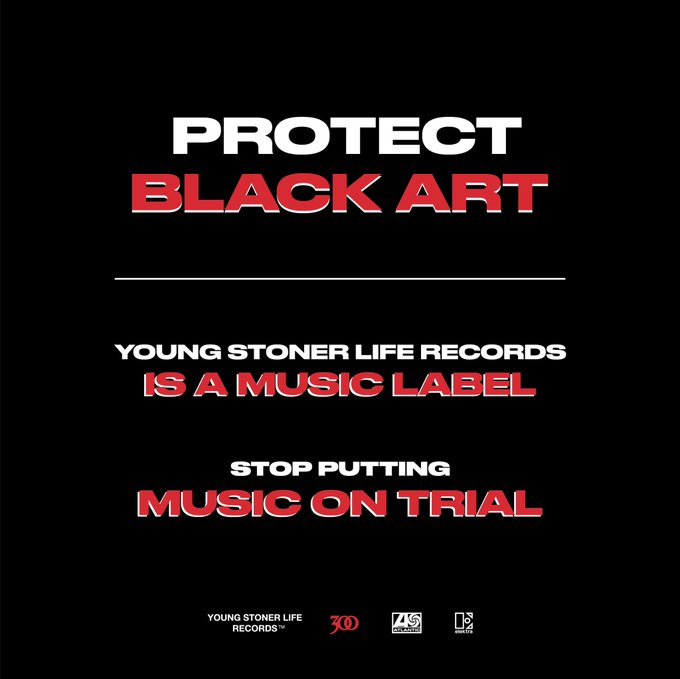

This is because rap is seen as inherently violent and the only art form targeted this way. Usually, when prosecutors use lyrics as evidence, it’s because there’s a lack of factual connection to the alleged crime as a form of character evidence to influence a jury. Ultimately, it’s a racist practice that prevents the defendant from getting a fair trial, the majority of whom are Black. It’s another way to punish Black communities and Black art. There has even been a petition, The Petition to Protect Black Art, which had been co-written by 300 Entertainment co-founder and CEO Kevin Liles and Atlanta Records COO, Julie Greenwald, is a document that asks both federal and state legislators to adopt bills limiting the use of rap lyrics as evidence.

According to a study conducted a few years ago by the American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU], almost 80% of cases examined as of 2013 admitted the defendants’ rap lyrics into evidence.

In 2014, the New Jersey Supreme Court decided the appeal of rapper Vonte Skinner whose lyrics were admitted at his trial for attempted murder and related charges. Lyrics that he wrote before the shooting occurred. After hearing the lyrics and other pieces of evidence, the jury convicted him. However, the appellate court concluded that the lyrics were highly prejudicial and should never have been admitted. The state of New Jersey then appealed but the state supreme court agreed: the verses should never have come into evidence.

A more recent case is that of Young Thug and Gunna YSL, where many are arguing that this is the latest instance of the criminal justice system unfairly tying rappers to violent crimes through their art. The grand-jury indictment identified Young Thug, Gunna, and 26 other associates as members of a “criminal street gang” YSL, or Young Slime Life. Allegedly, Thug is the founder of this street gang, which formed in 2012. The prosecution claims that YSL has affiliations with the Bloods and their subset gangs, Sex Money Murder or 30 Deep. The rapper founded the record label Young Stoner Life in 2016 as an imprint of 300 Entertainment.

Fani Willis, the district attorney overseeing this case, had said in a press conference “If you come to Fulton County, Georgia, you commit crimes, and certainly if those crimes are in furtherance of a street gang, then you are going to become a target and a focus of this district attorney’s office, and we are going to prosecute you to the fullest extent of the law.”

Gunna pleaded guilty as an acknowledgment of his musical association with YSL. His statements maintain his innocence despite the plea deal. Seven other defendants walked free in late December, each pleading guilty to a racketeering charge and said YSL was both a music collective and street gang, per their plea deal conditions.

Young Thug, on the other hand, remained incarcerated and is standing trial. All individuals named in the indictment were charged with conspiracy to violate the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act [RICO] by participating in a pattern of illegal activity to obtain money and property. The 56-count indictment claims that YSL members are involved in murder, attempted murder, armed robbery, aggravated assault, theft, drug dealing, carjacking, and witness intimidation. The indictment portrays Thug as some kind of mob boss, alleged to have committed multiple crimes that he has not been charged with.

Despite experts arguing that it is a violation of free speech, prosecutors have cited multiple songs as evidence of gang affiliation and racketeering activity in the YSL trial. Killer Mike said, in an interview with ABC News, “hip-hop is not respected as an art because Black people in this country are not recognized as full human beings.”

Young Thug has been behind bars with his requests for bond denied. Lance Williams, a professor at Northeastern Illinois University, told The New Yorker, “the optics look like gang stuff […] It looks ugly. But the reality is that most of it is just music.” Williams further stated, the RICO law is “this thing created for the Mafia now being used to indict young Black males who are flirting with the culture and the music, but who are not involved with any criminal enterprise.”

When asked about the use of rap lyrics as evidence in criminal proceedings, Willis said “if you decide to admit to your crimes over a beat, I’m going to use it. […] I have some legal advice: Don’t confess to crimes on rap lyrics if you don’t want them used, or at least get out of my county.” Despite bills introduced to limit the use of rap lyrics as evidence, Willis has vowed to continue using them.

Artists should be allowed the freedom to create and express themselves without worry that they’ll be arrested for their art. The use of rap lyrics as evidence should be called what it is: weak evidence used to target a primarily Black community. Art is inherently political, overtly or subtly. To use self-expression as evidence without actual evidence is to undervalue, undermine, and censor. If the jury or persecutor doesn’t have any substantial evidence beyond a few lines that could very well be made up, maybe it’s a weak case and they’re just looking for someone to blame.